Male and female He created them.

—Genesis 1:27

The Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon the man, and he slept; then He took one of his ribs and closed up the flesh at that place. The Lord God fashioned into a woman the rib which He had taken from the man, and brought her to the man.

—Genesis 2:21-22

To explain away this seeming contradiction, later writers of Jewish mysticism proposed that the first chapter is referring to a separate woman; that God had created a partner for Adam before Eve named Lilith who later rebels after refusing to mate with Adam in the missionary position, insisting that she be on top (it should come as no surprise why feminists love her). Never coming to an agreement, Lilith leaves the garden and becomes a demon. Her name appears once in the Bible, Isaiah 34:14, which is believed to refer to a demoness of the night. It is therefore more than likely that Lilith is based off of the Babylonian night demon Lilitu, a succubus who seduces men in their sleep. Her name is also listed among other monstrous creatures in a fragment of The Dead Sea Scrolls. While her demonic identity is known from such early sources, including the Kabbalah, the first and primary source of her story as Adam’s fallen wife comes to us from a medieval text known as The Alphabet of Ben Sira (8th-10th century CE):

When God created Adam and saw that he was alone, He created a woman from dust, like him, and named her Lilith. But when God brought her to Adam, they immediately began to fight. Adam wanted her to lie beneath him, but Lilith insisted that he lie below her. When Lilith saw that they would never agree, she uttered God’s Name and flew into the air and fled from Adam. Then Adam prayed to his Creator, saying, “Master of the Universe, the woman you gave me has already left me.” So God called upon three angels, Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangelof, to bring her back. God said, “Go and fetch Lilith. If she agrees to go back, fine. If not, bring her back by force.”

The angels left at once and caught up with Lilith, who was living in a cave by the Red Sea, in the place where Pharaoh’s army would drown. They seized her and said, “Your maker has commanded you to return to your husband at once. If you agree to come with us, fine; if not, we’ll drown one hundred of your demonic offspring every day.”

Lilith said, “Go ahead. But don’t you know that I was created to strangle newborn infants, boys before the eighth day and girls before the twentieth? Let’s make a deal. Whenever I see your names on an amulet, I will have no power over that infant.” When the angels saw that was the best they would get from her, they agreed, so long as one hundred of her demon children perished every day.

That is why one hundred of Lilith’s demon offspring perish daily, and that is why the names of the three angels are written on the amulets hung above the beds of newborn children. And when Lilith sees the names of the angels, she remembers her oath, and she leaves those children alone.

—Alpha Beta de-Ben Sira 5.

This story of Lilith is one of my all time favorites in Jewish mythology, even if it does come from a period later than most others. It’s a prime example of a silly yet fascinating tale that originates from a biblical discrepancy that later theologians felt like they needed to mend.

Lilith returns to the garden as the serpent

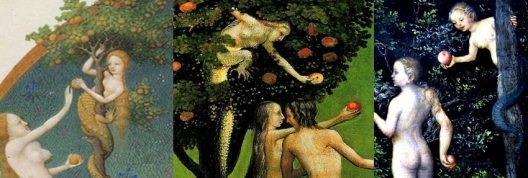

Some, though often late sources, say say that Lilith returned to the garden after her fall in the guise of the serpent, causing Adam and Eve to eat the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge.[2] What’s quite interesting is that this tradition appears (at first) to be supported by renaissance artwork of the Fall of Man in which the serpent is clearly depicted as a female. Upon investigation I was surprised just how many artists followed this convention, including Michelangelo; click the image to see an expanded gallery.

While it is argued by some such as John Bonnell and Jeffrey Hoffeld that these works are indeed of Lilith, I’m afraid to say that the evidence doesn’t hold up. The story of Lilith is a late Jewish tradition – whereas nearly all of the works depicting a female serpent are by medieval Christians. There are no supplementary writings that I’m aware of to indicate that the Lilith story was widely known in Christian circles; the only possible exception is in The Testament of Solomon (1st-3rd century CE) where a female demon curiously identical with Lilith is mentioned under the name Abyzou. It is the opinion of most art historians that artists depicted the serpent in female form to identify it with Eve, serving as a metaphor for woman’s sexuality and weakness. Artist Melissa Huang perhaps said it best in her article on the sexualization of Eve:

Renaissance artists, by depicting the serpent as a woman, were both revealing their opinions of female sexuality and decisively blaming womankind for the fall. Women were perceived by Renaissance audiences to be weak, gullible, and inherently flawed; an ideal scapegoat. The only issue with casting Eve as a temptress is that she was originally tempted by the serpent. If Adam—a man—was tempted by Eve—a woman—who herself was tempted by the serpent—a man—then the blame ultimately falls upon the male sex. However, if the serpent becomes a woman, then woman is ultimately to blame.

The theory that the serpent was depicted as a woman so as to identify with Eve is confirmed simply by paying attention to the artwork itself, in which the serpent looks exactly like Eve (examples: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5). The last three pieces in the gallery above are the only ones which clearly are Lilith and are modern works.

So as fun as it may be to imagine these works illustrating Lilith due to the remarkable coincidence, it would seem that her tradition stayed within the confines of Jewish mysticism. It’s worth speculating however as to whether it was the paintings which inspired the idea among later writers that Lilith did return to the garden as the serpent.

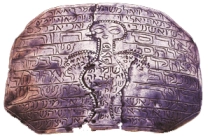

“Bind Lilith in chains!” reads a warning in Hebrew on this 18th-19th century C.E. amulet intended to protect an infant from the demoness. Lilith appears at center. The small circles that outline her body represent a chain. Beneath is a prayer: “Protect this boy who is a newborn from all harm and evil. Amen.”

Lilith in archaeology

Archaeological digs have revealed an abundant amount of amulets against Lilith, some dating back 1,500 years. The traditional use of such amulets against Lilith was widespread, and visitors to the ultra-Orthodox Mea She’arim section of Jerusalem will even today find protective amulets against Lilith available for purchase. Both the text and even the primitive drawings on the ancient amulet are still in use.

Lilith also appears in incantation bowls of the middle ages. These were bowls inscribed with incantation spells and placed upside down in areas of a home above the floorboards to demons trying to get in. The bowl seen below is from the 6th century CE and was made by an occultist to protect a woman and her husband from Lilith.[3] If you click the image to enlarge you’ll see a faint drawing of Lilith in the center. The Aramaic inscription reads:

In the name of the Lord of salvations. Designated is this bowl for the sealing of the house of this Geyonai bar Mami, that there flee from him the evil Lilith, in the name of “Yahweh El has scattered”; the Lilith, the male Lilin and the female Liliths…Be informed herewith that Rabbi Joshua bar Perahai has sent a ban against you…You shall not again appear to them, either in a dream by night or in slumber by day, because you are sealed with the signet of El Shaddai….Amen, Amen, Selah, Halleluyah!

Such earlier inscriptions reveal that “lilith” was also a generic term for a female demon among a class of demons of the night called “liliths”, both male (“lilin”) and female (“lilith”). It has also been suggested that the plural term of both sexes refers to Lilith’s demonic offspring that she bore with the demon prince Samael and/or from the semen of men while they slept after instituting wet dreams. A clearer and arguably more entertaining depiction of Lilith is seen in the center of this larger incantation bowl to the right.

Such earlier inscriptions reveal that “lilith” was also a generic term for a female demon among a class of demons of the night called “liliths”, both male (“lilin”) and female (“lilith”). It has also been suggested that the plural term of both sexes refers to Lilith’s demonic offspring that she bore with the demon prince Samael and/or from the semen of men while they slept after instituting wet dreams. A clearer and arguably more entertaining depiction of Lilith is seen in the center of this larger incantation bowl to the right.

One interesting image that commonly pops up in relevance to Lilith is the Babylonian “Queen of the Night Relief” (a.k.a “Burney Relief”) dating to the 19th-18th century BCE. I’ve noticed that many unscholarly websites will post this image identifying it – without a shadow of a doubt – as the Lilith of mystic tradition. Of course, this can’t be true as our Lilith, Adam’s first wife, doesn’t appear explicitly until the middle ages. It could be the Babylonian demoness Lilitu, however this claim is largely outdated, based originally on a misreading of an antagonist of the goddess Inanna (ki-sikil-lil) found in an obsolete translation of The Epic of Gilgamesh. While the debate continues, most scholars today identify her as either Inanna (Ishtar in Akkadian) or her sister Ereshkigal. I personally find the former more convincing for a number of reasons. Despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary, I still find it fun to imagine Lilith as Adam’s first wife originating early on, only to be edited out by later scribes.

One interesting image that commonly pops up in relevance to Lilith is the Babylonian “Queen of the Night Relief” (a.k.a “Burney Relief”) dating to the 19th-18th century BCE. I’ve noticed that many unscholarly websites will post this image identifying it – without a shadow of a doubt – as the Lilith of mystic tradition. Of course, this can’t be true as our Lilith, Adam’s first wife, doesn’t appear explicitly until the middle ages. It could be the Babylonian demoness Lilitu, however this claim is largely outdated, based originally on a misreading of an antagonist of the goddess Inanna (ki-sikil-lil) found in an obsolete translation of The Epic of Gilgamesh. While the debate continues, most scholars today identify her as either Inanna (Ishtar in Akkadian) or her sister Ereshkigal. I personally find the former more convincing for a number of reasons. Despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary, I still find it fun to imagine Lilith as Adam’s first wife originating early on, only to be edited out by later scribes.

Sources and Further Reading

- Where Does the Legend of Lilith Come From?

- A great article on Lilith by the Bible Archaeology Society

- Resources on Lilith by Professor Alan Humm

- Jewish Virtual Library on Lilith

- Lilith Spotlight by the Museum of Biblical Art

- “Samael, Lilith, and the Concept of Evil in Early Kabbalah”

- British Museum on “The Queen of the Night Relief”

- Book: Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism by Howard Schwartz

[1] Schwartz, Howard. Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism (p. 216-217).

Primary sources: Alpha Beta de-Ben Sira 5.

[2] Rossetti, “Eden Bower,” in Poems (Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1873), pp. 31–41.

[3] Patai, Raphael. The Hebrew Goddess (p. 225-26).